Beneath the Gilded Surface: Class and Color in Victorian Society

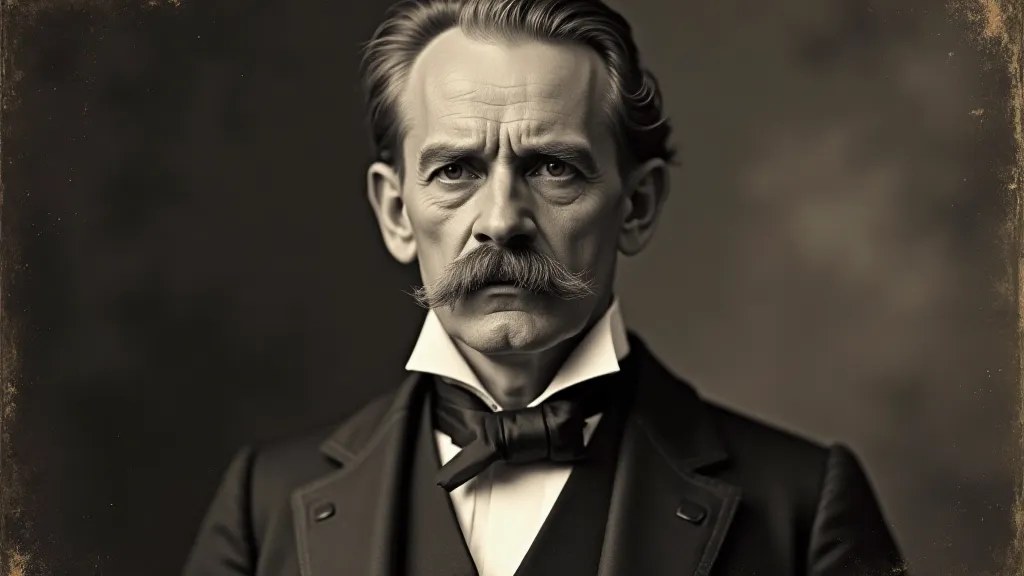

The Victorian era – a time of burgeoning industry, elaborate mourning rituals, and an insatiable appetite for portraiture. Photography, still in its infancy, rapidly became a key player in this societal drama. Early photography, however, presented a monochrome world. While black and white held a stark beauty, a yearning for something more, something closer to reality (or at least, to a romanticized version thereof), fuelled the development of hand-tinting techniques. But these weren't simply aesthetic choices; they were subtle, yet powerful, markers of social status, a whispered language spoken through the hues applied to a photographic surface.

Imagine, if you will, the clatter of a printing press, the pungent smell of developing chemicals clinging to the air. My grandfather, a meticulous clockmaker and amateur historian, often told me stories of his own grandfather, a railway worker who painstakingly collected early photographs – mostly portraits of his family, carefully preserved in a leather album. Most were simple albumen prints, their surfaces cool and grey. But a few… a few bore the unmistakable glow of hand-tinting. That subtle blush on a lady's cheek, the vibrant green of a garden, the rich, mahogany tone of a gentleman’s waistcoat – these weren't accidental. They were deliberate applications of color, a visual cue to a person’s place in the social hierarchy.

The Early Days: Brownstones and Barely-There Tints

Early hand-tinting, primarily in the 1860s and 1870s, wasn’t the flamboyant, full-colorization we might imagine. The techniques were rudimentary, often involving dry pigments applied with brushes or cotton swabs. These “trembleuse” tints – so named for the slight trembling of the hand required to apply them evenly – were typically limited to subtle highlights: rosy cheeks, a touch of color to lips, or a faint blush on a shawl. These weren’t intended to mimic exact colors, but rather to impart a sense of warmth and vitality to the otherwise austere image. The process was time-consuming and required a deft hand, making it a relatively expensive addition to a photograph’s cost. Therefore, the most basic tinting was primarily reserved for the middle class, who desired a touch of refinement without the extravagance of the upper echelon.

The Rise of "American" and "Continental" Styles

As photography matured, so too did the techniques of hand-tinting. By the 1880s, two distinct styles emerged: the “American” and the “Continental” methods. The American style, characterized by its use of aniline dyes, offered a wider range of colors, allowing for more vibrant and intense hues. While the dyes were prone to fading over time (a significant drawback that continues to affect their preservation today), their accessibility made them a popular choice among studios aiming to attract a broader clientele. These more saturated colors were often applied to clothing and decorative elements, showcasing a certain level of prosperity and a willingness to embrace contemporary trends.

The Continental style, particularly prevalent in Europe, favored a more restrained palette, often utilizing oil-based pigments. The resulting images possessed a softer, more painterly quality, evoking the feel of an Impressionist painting. These tints were generally more permanent than aniline dyes, though they still required careful handling and preservation. This meticulous approach, coupled with the higher cost of materials, generally positioned Continental-style tinting as a luxury service, appealing to a wealthier, more discerning clientele. The subtle artistry of these tints signified a respect for tradition and a refined sensibility.

The Language of Color: Conveying Status and Style

The choice of colors themselves carried meaning. Red, for example, symbolized prosperity and social standing, appearing frequently on ladies’ gowns and gentlemen’s coats in portraits intended to project an image of success. Green, often used to represent nature and tranquility, was common in family portraits taken outdoors, suggesting a comfortable, rural lifestyle. The saturation of the colors was also telling; a deeply saturated red signaled a bolder, more assertive personality, while a muted rose suggested a more demure and refined character. The application itself – was it a delicate blush or a vibrant splash – communicated volumes about the subject’s social ambition. Even the choice of background – a simple studio backdrop versus a painted landscape – spoke of economic means.

It’s remarkable to consider how much information is encoded within these seemingly simple images. My grandfather’s railway worker ancestor, meticulously preserving those tinted portraits, wasn't simply collecting photographs; he was collecting fragments of history, visual testaments to the social dynamics of his time. He knew, instinctively, that those subtle hues spoke volumes – about family pride, economic status, and the delicate dance of Victorian society.

The process wasn't always straightforward, of course. There was a constant tension between artistic expression and the expectations of the sitter. A portrait was not just a likeness; it was a carefully constructed representation of self, shaped by social conventions and economic realities. A photographer needed to be skilled not only in the technical aspects of image-making, but also in understanding the nuances of Victorian etiquette and social signaling.

Restoring these tinted photographs is an exercise in understanding that language. It’s not enough to simply remove dust and scratches; one must carefully analyze the existing color palette, assess the stability of the dyes, and make informed decisions about how to preserve the integrity of the original artist’s vision. And sometimes, it's best to leave the tints as they are, allowing them to whisper their story across the decades – a quiet testament to a time when even a touch of color could reveal a world of social meaning.

A Legacy of Subtle Expression

The practice of hand-tinting eventually declined with the rise of color photography in the 20th century. Yet, the legacy of these tinted portraits remains – a poignant reminder of a time when photography was not just a tool for documentation, but a medium for subtle expression and social commentary. Each faded hue, each delicate brushstroke, holds a fragment of Victorian history, waiting to be rediscovered and appreciated. The painstaking craft is a beautiful encapsulation of the intersection of art and class, an enduring echo of a bygone era.